What is animal representation?

What does it mean for human understanding of animals, the human-animal relationship and,

ultimately, what does it mean for animals?

This page outlines what is meant by animal representation in art, in culture, in visual communication, and why it is significant in how we understand, or make sense of human society’s, and societies’, relationship with non-humans.

References and links to further information are provided throughout and summarised at the end of this article.

Introduction to Animal Representation

If we are to discuss animal representation it it helpful to understand it in context of representation in general. Representation means to depict something and to conjure up meaning through that depiction. Context matters to representation; who is the reader and where and when a text is seen affects how it is understood.

“In general terms, the term ‘representation’ refers to the depiction or portrayl of something in any medium that then makes a text.” (Chandler, 2020a).

Daniel Chandler 2020

Representation refers to the making of meaning through a portrayal, a description, through art, story-telling, literature, advertising, even a conversation and so on. Representation is concerned with shared cultural understanding, how meaning is understood and accepted within society, how and where meaning is created, contained and reflected within a text, written, spoken, aural or visual texts.

Here we will concentrate on visual representation and the making of meaning through visual texts such as a painting, photography, advertiisng, comics, illustration and so on. and specifically that of animals, but it is important to acknowledge that concerns and interest around representation overlap through all media and outlets for representation.

Language is a system of representation

Sociologist and psychologist, Stuart Hall explains how language is a shared system of signs and symbols; it ‘operates as a representational system’ (Hall 1997 p1). These signs and symbols can be sounds, words, musical notes, objects and images, and any components of these. For example, in an illustration has meaning and it is made up of component signs and symbols that also contain meaning. Line, colour, shape, texture, objects, scale and so on all work to create an idea, a feeling, a response; they work as language to create meaning.

Why do issues of representation matter?

Derrida and how linguistics contribute to unsustainable ways of thinking and illustration is a form of speech.

The need to challenge unsustainable thinking within culture, by question, analysis and reflection on our own work.

Decartes Bete machine wherby he evaluated animals with machines, functioning but not experiencing, not feeling.

1637

anthropocentric binaries and pradigms of happy cute lives. in his analysis of Derrida’s dream of ecolingustics, Moser calls them ‘deadly delusions’ https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/sem-2020-0027/html.

Are these cute images examples of these deadly delusions – certainly barthes would consider them at least myth – with thie runderlying lying and second-level semiotic meaning – that decieves and obfuscates a terrible truth – and therefore perpetuates it unseen, unknown, ignored.

Moser argues that it was indeed an example of ecocentric thinking – whereby we put ecological concerns before thos eof the individual. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/sem-2020-0027/html

Definitions

To begin, let’s look simply at dictionary definitions.

Collins online dictionary describes representation as

- anything that represents, such as a verbal or pictorial portrait

- anything that is represented, such as an image brought clearly to mind

Word hippo, a great resource for definitions and synonyms, lists the following.Representation

noun: The representation of something through art or imagery

And

noun: The description or portrayal of someone or something in a particular way

So, here we can begin to see the word ‘representation’ in the context of image making, in the context of illustration and visual communication. However, these definitions do not explain why we understand what we understand when we see an image; how do we make meaning when we create and when we view an image? Meaning is not certain, fixed but representations can have many meanings.

Therefore, animal representation is any depiction or portrayal, in any medium, that brings to mind an animal; it is any impression or description that denotes, describes, embodies, symbolises or depicts an animal, and furthermore, it is how that image is understood, what meaning is made of it, what is read, perceived and confirmed by it.

Representation and making meaning

“Every representation is motivated and historically contingent.” (Chandler, 2020c)

Daniel Chandler

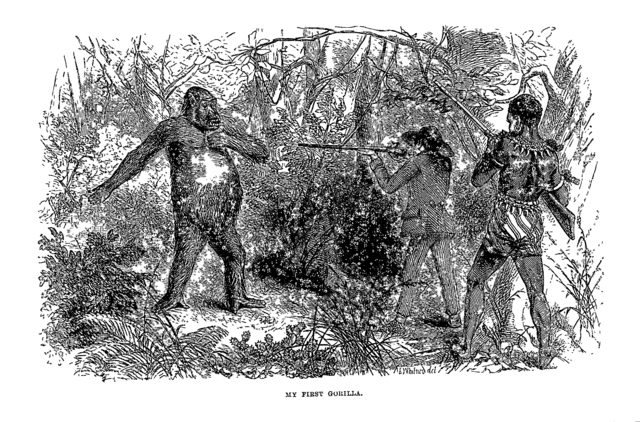

Understanding meaning, and making meaning, depends upon the physical attributes of an image but also the artist’s and the viewer’s experiences. We need more than recognition of the visual elements to make meaning; perception requires more to make meaning. For example, this image, an etching by Victorian explorer Paul Du Chaillu,shows him shooting his first gorilla. This illustration was for a children’s book and was intended to demonstrate the thrill of hunting and the bravery of the hunter; it was intended to regail heroic tales of empire. With contemporary perpsectives, we are much more likely to see an horrific image of trophy hunting and definitely not appropriate for a children’s book. As an image celebrating empire we can clearly see how it was a form of propoganda – albeit unintentional – but witht he distance of time the imagis seen with objective eyes, eyes unencumbered by the dominant ideology of the time. Furthermore, seen thorugh an animal advocate lens, it is a deeply troubling image.

The Stories we tell

“Representations which become familiar through constant re-use come to feel ‘natural’ and unmediated, and can even shape what we accept as reality (at least within a genre).” (Chandler, 2020b)

Hall remarked how, in part, we give things meaning by how we use them, and in part we gives things meaning by how we represent them.

“We give things meaning by how we represent them – the words we use about them, the stories we tell about them, the images of them we produce, the emotions we associate with them, the ways we classify and conceptualize them. ” (Stuart Hall 1997 p3)

Seeing and thinking

The meaning we make from an image, and from the images around us, is constructed from our own experiences, what we have been taught, what we have learned, and in turn we make images, through art, photography, painting and so on, that reflect our own understanding of the world, our own way of ‘seeing things’.

The image of animal

In his book Animals on televison, Professor Brett Mills remarks how little is written about the visual representation of animals (Mills, 2019). He reminds readers that “the planet teems with non-human beings . . . they’re out there” and through television we bring a host of animal representations, that include the animal stars of Planet Earth to Patrick the starfish in Spongebob Squarepants, into the home. (Mills, 2019).

Professor Steve Baker invites readers to try to envisage the whole of our contemporary culture and then call to mind all the ways in which animal representations, visual and other, figure in that culture and what those representations might reveal about human attitudes toward animals.In Picturing the Beast, Baker lays out his enquiry into these animal rpresentations.

that, ‘much of our understanding of human identity and our thinking about the living animal reflects – and may even be the rather direct result of – the diverse uses to which the concept of the animal is put in popular culture, regardless of how bizarre or banal some of those uses may seem. Any understanding of the animal, and of what the animalmeans to us, will be informed by and inseperable from our knowledge of its cultural representation. Culture shapes our reading of animals just as much as animals shape our reading of culture. We use representations to think with animals, we use their likenesses to describe and form human feelings, thoughts and identity mush more than we describe animlas to help us think about them. Consider children’s picture books and the animal representations described within them and how we use the animals’ image as stand ins, as metaphor; we use their images to think with, and intertextuaity and failure to re-examine concepts ideas and beliefs are repeted and reinforced over and over.

How we think about animals affects the making of representations, how we depict them, and how we depict them affects how we think about them. Being an animal bound up in human culture, as dairy cow, family pet, wasp and so on depends more on how humans perceive them, value them rather than even their own biology may dictate. Human culture describes and determines the life of animal and visual culture, visual communication must share the responsibility fo rhow animlas are understood.

Reinforcing ideas of dominance

Issues of representation are urgent for oppressed groups because representations act as propoganda for dominance; transforming and resisting oppressive representations is part of the struggle toward liberation.

Carol J Adams and Lori Gruen 2014

Strategies for animals

Leslie Irvine points out that within human culture, species fall in to good and bad in human terms, yet, it almost never will save them, good or bad.

Animals have different meanings, largely because we categorize them along a hierarchy of the value that Arluke and Sanders call the sociozoologic scale. Ever since Aristotle developed what he called the scale of nature, we have ranked animals in various ways, always below human beings of course. Elwood Darwin another is after him challenged systems that place humans above all other creatures. The idea of a hierarchy remains powerful. We make distinctions not only between humans and animals, but also among animals.

Here’s the takeaway. The sociozoologic scale is a system of meaning that rank species as good or bad according to their social, cultural, and moral value to humans. It influences not only how we think about animals, but also how we treat them.

Some animals are constructed as merely human. This is especially the case for domestic dogs and cats often considered companions, best friends, or family members. Horses too would land a place at five. – Leslie Irving

Interestingly in picture books they are more likely to have their own real lives represented – perhaps because their true lives are safe to look at – we can tell the truth.

Leslie Irvine says that what an animla means depends on time, place and culture. https://www.coursera.org/learn/animals-self-society/lecture/ReaW4/animals-and-cultural-representation

Dismantle the stereotypes within representation

Creating images that counter the stereortype. Hall argues that to create theopposite can reinforce the original stereotype by bringing it to mind. And Barthes states that . . .

Wolf illustration reflects years of tradition and myths

In attempting to tell stories about ourselves we we surround the species, the wolf, the pig, the fox with ideas about their identity to us.

two approaches – to show they are not athreat to us

to show we are a threat to them

then Image what a story would look like if we illustrated animals using efforts to describe from thier perspective

In defense of animal representation

It could be argued that reality is not the intentionof illustration, or for example, the picture book farm is not intended to describe a real world farm. But, representation is complex; we could then ask what is the intention of illustration, of an illustration? An image purports to present some kind of reality. For example, Aesop’s fables use animal referents to tell moral lessons to young readers; we are using the idea of animal, albeit imaginary and speaking, to tell our ideas of our human reality. the film Avatar used a wholly imaginary world and fantastic beings to tell a human centered story of diversity and prejudice and oppression.

To stay silent is also a position; to stay silent, to not draw animals, is a position of supporting the status quo

Adams, C., Gruen, L. (2014) Ecofeminism: Feminist Intersections with Other Animals and the Earth (p. 25). Bloomsbury Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Berger, J. (2008a) (1972) Ways of Seeing (Penguin Modern Classics) . Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition. location 25

Berger, J (2008b) (1972) Ways of Seeing (Penguin Modern Classics) . Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition. location 46

Berger, J (2008c) (1972) Ways of Seeing (Penguin Modern Classics) . Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition. location 46

Chandler, D., (2020a)